Frida Kahlo: Magical Realist?

by Katy Wimhurst

If Latin American literature is renowned for its magical realism, then are there any equivalents in the visual arts? An obvious choice is Frida Kahlo (1907-54), a painter now so famous that Madonna collects her works, and whose startling images still seem fresh despite having been painted over half a century ago. But is Kahlo a magical realist? Arguably so. For one thing, as in magical realism, her paintings are rooted in the real world but also contain fabulous elements, and the real and the fantastic interweave in a seamless manner.

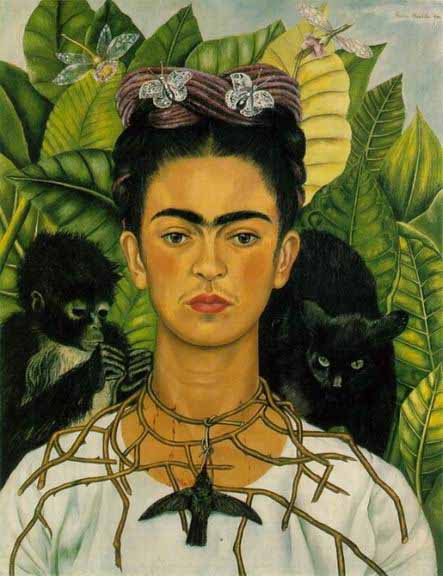

In Self-Portrait (1940) (see Figure 1), one of many paintings in which Kahlo uses herself as the main subject, her face, with its trademark joined-up black eyebrows and faint moustache, stares out of the painting. Her eyes are slightly downcast and she is painted against a lush backdrop of vegetation and animals. A monkey of the kind Kahlo owned as a pet sits at her right shoulder while a black cat peers over her left. Her hair is pulled back and piled up in a traditional Mexican style, seemingly held in place by lace-winged butterflies of silver and gold, while above her—and here we really start to move into the realm of 'the fantastic'—are forms that look like half-flowers, half-insects. Around Kahlo's neck hangs something odd, disquieting: a necklace made not of beads but of a lattice-work of thorns that prick at her neck, causing droplets of blood to fall down it; and from the tip of the necklace hangs not a precious stone but a (dead?) hummingbird.

Figure 1: Self-Portrait 1940

This is a disturbing self-portrait which hints at personal suffering in a quixotic, unsentimental way—Kahlo's paintings can't be fully understood outside the context of her life and pain, which I discuss more below. Some might say Self-Portrait has more in common with Surrealism than magical realism, especially the Surrealist penchant for dream imagery, strange juxtapositions and rendering familiar objects in unfamiliar ways (in contrast to magical realism which tends to make the extraordinary seem everyday). But although Surrealism was keen to claim Kahlo as one of its own—Andre Breton was especially enamoured by her art—she always distanced herself from the movement, asserting, "I don't paint my dreams. I paint my reality". Kahlo's desire to present her reality in a symbolic way—a complex reality that plain realism was inadequate to convey and that conflated the inner and outer dimensions of life—brings her closer in sensibility to magical realism, which also involves an expanded idea of reality, uses complicated symbolism and, as Wendy Faris (1995) has suggested, exists at the intersection between two worlds, the extraordinary and the ordinary, the magical and the 'real'.

In portraying Kahlo's reality in a symbolic manner, Self-Portrait, like other works by the painter, was influenced by techniques from European modernism, however, such as aspects of the visual language of Surrealism and avant-garde trends like using a flattened perspective. But Kahlo's works more importantly drew on sources from Mexican folk art and myth. The lattice of thorns bring to mind the iconography of popular Catholicism—in Mexican churches, Jesus's passion, particularly his crown of thorns, is depicted graphically, with droplets of blood dripping down his body; and the hummingbird was a common theme in pre-Columbian myth, the Aztec deity Huitzilopochtli, god of war, being associated with the bird, for instance. Kahlo's paintings, which have a folk-like quality and were generally produced on tin rather than on canvas, were also influenced by retablos, small votive paintings made by Mexican journeymen artists in a tradition that dated back to the colonial era. retablos were painted on tin and created to thank a holy being or saint for saving a person from some peril or illness. The affinity between Kahlo's work and retablos is most significantly one of sensibility: as Hayden Herrera (1983), Kahlo's biographer, has suggested, "both [art forms] record the facts of physical distress without squeamishness. Both evince a kind of deadpan reportorial directness."

Although in her lifetime Kahlo painted primarily for herself (most of her artistic fame was posthumous), by combining Mexican and modernist themes she ended up (somewhat inadvertently) creating a very Mexican form of modern art. In this way, her work was a precursor of Latin American magical realism: a writer like Gabriel García Márquez drew on European modernists like Kafka, but was also inspired by the folklore and oral traditions of his native Columbia, and he helped engender a form of literature which was originally hailed as quintessentially Latin American but which, like Kahlo's art, has subsequently achieved more global recognition.

But doesn't the comparison between magical realism and Kahlo have its limits? For one thing, her work could be seen as distinct from that of García Márquez in being painfully autobiographical—her art can't really be comprehended outside her own often traumatic experiences, especially the horrible accident she had as a teenager when, during a tram crash, a metal pole pierced her body, leaving her partially crippled, in constant pain and unable to have children. Her suffering was later compounded by a tempestuous marriage to the (then-famous) Mexican artist Diego Rivera, a man who was frequently unfaithful to her, including with her own sister Christina. Kahlo responded by having affairs with both men and women, including with Leon Trotsky.

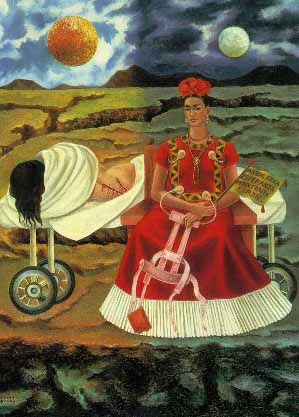

In Tree of Hope (1946) (see Figure 2) two Frida Kahlos are presented to the viewer. One is lying naked on an operating table, the horrific scars of an operation showing on her back. The other is sitting upright in a Tehuana dress (a Mexican costume dress of the sort Kahlo sometimes wore), and in her left hand she holds the back brace Kahlo was forced to wear to support her damaged spine, while in her right hand is a flag that carries the words, 'Tree of Hope: Stand Firm'. The combination of pictorial and written elements is suggestive of retablos, which contained words as well as images. The setting of Tree of Hope is a Mexican desert, the cracks in its earth echoing the scars on Kahlo's naked body. The painting is divided into night and day, the Tehuana Frida sitting under the moon, the operated-on Frida lying under the sun. The use of night and day brings to mind paintings of the Surrealist Réné Magritte, but it is also consistent with Aztec and Mayan mythology, especially the idea of the eternal battle between night and day. In Tree of Hope it is as if two Frida Kahlos, two distinct selves (and the struggles between them), are being presented, one closer to her public persona, the courageous and exotically dressed Mexican woman who identified strongly with her homeland, and the other the more private self, the woman who suffered relentless pain (Kahlo once joked she held the world record for medical operations).

Figure 2: Tree of Hope 1946

To the Mexican writer Carlos Fuentes, Kahlo's pain is not purely personal, though. Rather, the way she combined Mexican themes with her own suffering so regularly suggests to Fuentes that her pain is symbolic of that of the Mexican nation—the damage caused by colonialism, the pervasive poverty, especially among indigenous people, and the endless political upheavals, including revolutions, which have torn the country apart. If Kahlo's work is about her beloved Mexico, it again has affinities with Latin American magical realism, which sought to communicate, in a manner that merged the real and the magical, something about the nature of Latin America, with its turbulent history and odd mixture of European and non-European, pragmatic and magical cultures. Indeed, Carlos Fuentes suggests that Kahlo's work is a powerful reminder of how, in everyday Latin America, there is "a spontaneous fusing of myth and fact, dream and vigil, reason and fantasy" (1995:14).

References

Faris, Wendy (1995) 'Scheherazade's Children: Magical Realism and Postmodern Fiction', in Zamora and Faris (1995) Magical Realism: Theory, History, Continuity, Duke University Press.

Fuentes, Carlos (1995) 'Introduction', in Frida Kahlo, The Diary of Frida Kahlo: An Intimate Self-Portrait, London: Bloomsbury.

Herrera, Hayden (1983) Frida: A Biography of Frida Kahlo, New York/London.

Story Copyright © 2008 by Katy Wimhurst. All rights reserved.

Previous: In the Clouds by Aliya Whiteley | Next: In the Clouds by Aliya Whiteley

About the author